Articles

Videos

More Research

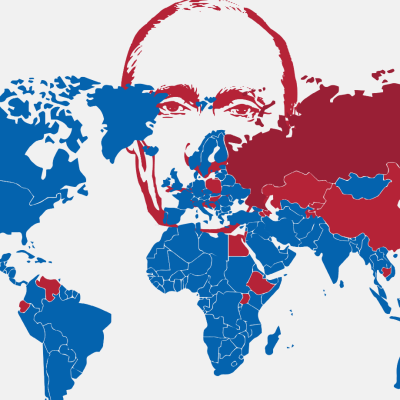

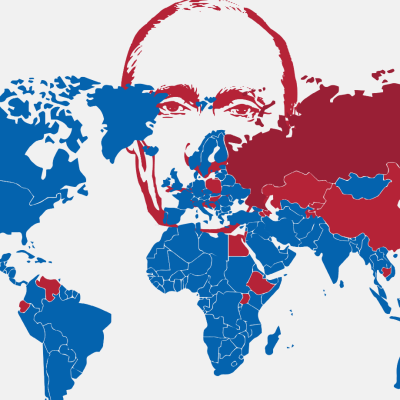

The first issue of Kremlin Influence Quarterly looks at malign influence operations of Vladimir Putin’s Russia in the areas of diplomacy, law, economy, politics, media and responses to the COVID-19.

The opening essay, “Russian Malign Influence Operations in Coronavirus-hit Italy” by Anton Shekhovtsov, argues that, by sending medical aid to Italy—a country that was hit the hardest by the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020,—the Kremlin pursued a political and geopolitical, rather than a humanitarian, agenda. The Kremlin sent aid to Italy against the background of the rising distrust towards the EU in Italy as Europe was late in demonstrating solidarity with the Italian people suffering from the pandemic. The Kremlin’s influence operation was meant to show that it was Russia, rather than the EU or NATO, that was the true friend of Italy. Putin’s regime hoped that it would undermine Italy’s trust in the two international institutions even further and strengthen the country’s opposition to the EU’s sanctions policy on Russia.

In their chapter on Russian-Hungarian diplomatic relations, Péter Krekó and Dominik Istrate write that—while Putin’s Russia often had an unhealthily close relationship to some former Hungarian prime ministers—Russian influence over Hungary has gradually expanded since Viktor Orbán returned to power in 2010. The authors note a huge asymmetry that characterizes the relationship between the two countries, as the benefits are much more obvious for the Russian state than for Hungary. The diplomatic relations seem to be only the tip of the iceberg in the non-transparent bilateral ties—with the frequency of the meetings and some background information suggesting a shady relationship as deep as the abyss.

In the first part of his essay on Austrian-Russian business relations, Martin Malek focuses on their political framework conditions, as well as side effects and consequences over the past two decades. The author asserts that the supply of natural gas and crude oil from Russia to and via Austria plays a special role in this relationship, since it accounts for the lion’s share of Moscow’s exports, and it is also relevant for other EU countries which likewise purchase Russian gas. Furthermore, the author shows that trade relations between Russia and Austria advance Russia’s malign influence.

Georgy Chizhov’s chapter looks at the workings of the pro-Kremlin media in Ukraine. The author identifies these media and analyzes narratives they promote in order to discredit democratic values and institutions in Ukraine and in the West, and to sow distrust both inside Ukrainian society as well as regarding European and American partners. He also examines Ukraine’s attempts to resist Russia’s information influence.