Interview with Denis Sokolov conducted by Lidia Mikhalchenko.

On April 20, 2020, a spontaneous protest took place in North Ossetia. Official statements by the government described them as violation of public order aimed to subvert the quarantine measures. Is this an accurate description?

– Well, the protest was not so spontaneous in reality. Vladimir Cheldiev, an opera singer usually residing in St. Petersburg, published a call to the residents of Vladikavkaz to gather and protest quarantine.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=amZdfuntG8Q

Vadim has recently returned to Ossetia to tend to family matters and over the past few months has emerged as the face of protests in Ossetia. Two days prior to the protest, he was detained on charges of either “willingly spreading false information on the coronavirus”, or for “exerting physical violence against law enforcement representatives.” (Cheldiev is now facing charges under part 1 of article 381 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, use of mild violence against a government representative).

Vadim Cheldiev rose to fame in 2018, in the aftermath of a fire at the Elektrotsink (Электроцинк) factory. Using his social media accounts, he issued calls to close the factory, started conducted negotiations with the Region’s Head Bitarov, criticized local officials as being “anti-people” and vented about global consipracies.

Vadim Cheldiev’s videos resonate with a widespread folk mythology that all evils (from environmental degradation, loss of respect for elders, dishonorable conduct by women) stem from departure from the original “Indo-European” traditions. Cheldiev’s accounts in Telegram and Instagram have tens of thousands of subscribers and readers. Cheldiev has an incredible charisma. During protests, one of the demands voiced by the crowds was Cheldiev’s release from detention.

This activist and defender of traditional values believes that there is no pandemic; that Covid-19 is a conspiracy concocted to enslave simple people; that the Russian government has turned the country into a colony for the West.

What’s different about the Ossetian protests is that here, out of the blue, a deeply traditional ethnos, whose worldviews and believes have been long overlooked and dismissed by officials, experts and journalists – started a riot. This is an ethnos living in a harsh reality, full of inconvenient and even outlawed beliefs: extremism, conspiracy theories, inciting hate toward other social and ethnic groups, condoning Stalinism, hatred of the elites. Of note, Russian riot police from OMON, Rossgvardiya, FSB operatives and many other officials live in the same exact world. If you pose a question on fears of having a microchip implanted during vaccination, the percentage of affirmative responses among the protesters and among those dispersing the protest, both on the streets and by issuing decrees from cushy offices, would be about the same.

The coronavirus quarantine measures and the accompanying administrative chaos have achieved something that opposition politicians and civil activists had failed to achieve 20 years ago, – they have awakened and mobilized the people. Of course, this didn’t happen overnight. The incomes have been falling for several years straight; the quality of governance has been declining for several decades; regional officials, local businesses and even criminal networks have degraded. All of these factors have contributed to the shrinking opportunities for social advancement for ambitious youth.

Financial flows and oil exports, that have previously supported the system, have collapsed. Cab drivers, small business owners, their employees, all those who had been living hand-to-mouth, are now left without any means to support themselves. All of this is happening against the backdrop of two restaurants that continued their operation even during quarantine, and both, not surprisingly, belong to the head of the Republic.

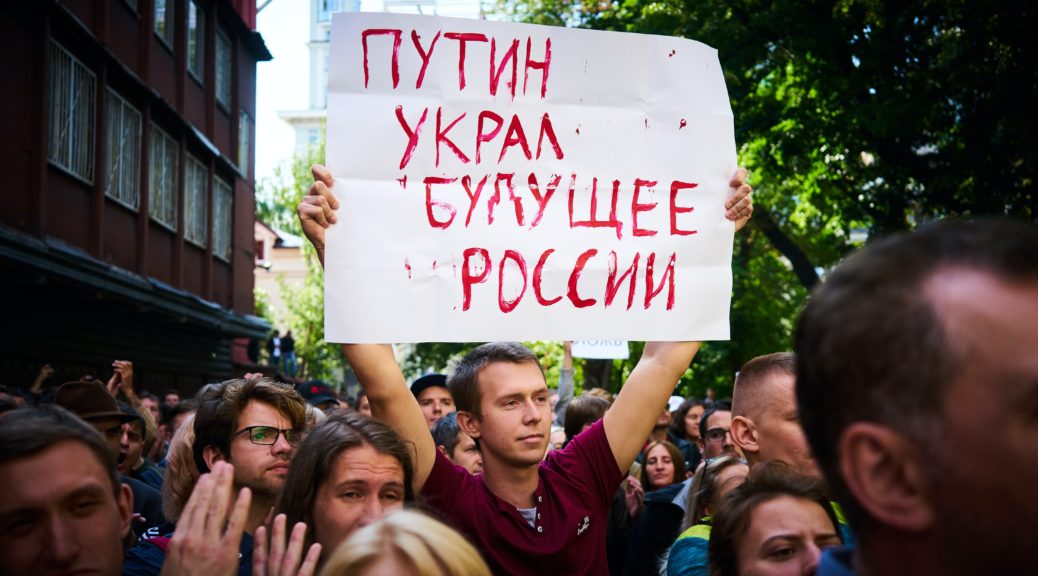

The Vladikavkaz protest is a protest against the elite and against modernization (as modernization in the minds of the people aims to advance the elites’ interests). This is an uprising not only against the region’s head Vyacheslav Bitarov, but also against the current system as a whole.

This protest cannot be stopped by arrests (according to the official statistics, 69 people have been detained at the April 20, 2020 protest), puny handouts (159 families have reportedly received cash aid the day after the protest). Such half-measures only further enrage the people. It is possible, however, that rescinding the quarantine measures would temporarily dampen the wave of dissatisfaction.

The police, Rossgvardiya and the Cossacks that can be successfully unleashed against “foreign agents” and “unhappy urban dwellers” are not effective against a people’s uprising. One of the Rossgvardiya divisions from the Krasnodar Kray outright refused to dispatch units for the dispersal of the Ossetia protest; and after their shifts ended, the Vladikavkaz OMON had to be transported from the protest square to the barracks and not their homes, out of fear that they might join the protesters.

Are any influential political leaders directing the protests or emerging from them?

– There were no influential political leaders among the protesters in Vladikavkaz. Of course, there are many politicians who overtly or secretly oppose Bitarov inside the Republic’s parliament, and at various municipal government offices, and among Ossetia’s representatives in the Russian State Duma and in the Federation Council. Most regional influencers and opinion-leaders are also in opposition to the head of the Republic. However, this protest is against all elites. So, the political intrigue is focused on discrediting potential candidates that may vie for the post of the head of the region whenever it becomes vacant. Ossetian legislators in Moscow have taken a huge political hit for their vote for (or not voting against) the initiative to move the Victory Day parade to September 3, which is not only the end of the World War II but is also the day of mourning for the Beslan tragedy victims. However, all of these political games have lost their relevance for the time being. If the protest continues to grow, someone may attempt to reign it in, but that’s a different topic for discussion.

Is it fair to say that small businesses have taken the biggest hit from the quarantine?

– Yes, it is fair to say so. Small business is the source of sustenance for many in Ossetia. Small private cattle farms, vegetable gardens, orchards; and in urban areas – hair salons, markets, shops, restaurants, coffee shops. Protection racket income from these small businesses also supported criminal groups and the law enforcement. So those two groups are now in total alignment with the people.

Here, we have a situation where supposedly everything was shut down to fight the virus. At the same time, the restaurants owned by President Bitarov continue to operate.

Those with access to the administrative resource, levers, connections, take as much as they can without thinking twice. Federal chains such as “Pyatyorochka” or “Magnit” continue to operate; federal home goods stores remain open. Such businesses, by the way, are also perceived as part of the elite conspiracy against the people.

Why has Ossetia spawned so many coronavirus-deniers and corona-skeptics?

– The opera singer Cheldiev, whom we have discussed earlier, uncovered a story about a woman who died in a hospital from causes not related to the pandemic. The hospital administrators attempted to falsify the cause of death, even offered a bribe to the family of the deceased for their silence. Region’s doctors and health care workers are severely underpaid, the entire system is very corrupt, and in this situation they anticipated a direct benefit: 50,000 roubles for working with a coronavirus patient for the nurse, double that sum for the doctor, and there have been several nurses and doctors who have been handling the patient. But it’s a small city, so the ruse was debunked.

But that’s not all. The Kremlin propaganda can say what it wants on Russia Today. It can discuss how Russia is better than Europe and America in addressing the coronavirus; it can send formidable anti-virus dispatches to Italy and Serbia; it can sound outrage about the mass graves in Brooklyn; it can show the nightmare of the pandemic in the United Kingdom. But none of this would turn Russia into a developed country. None of this would restore the health care system that has been destroyed. Virus is a great fact-checker. The Russian government is unable to control the pandemic in our country or the number of victims neither organizationally, nor technologically. It is more likely to exacerbate the situation with sawing panic, or banning planned surgeries and providing health care to non-coronavirus patiens.

Russia is oftentimes favorably compared to Italy where there is a great proportion of recorded deaths. But in Italy, an average life expectancy is 85 years, and the average age of those perished from the virus is 82. In Russia, an average life expectancy is 72, so the majority of the Russian citizens die even before becoming a risk group for the virus at the age of 65-70.

North Ossetia, by the way, has the lowest life expectancy in the Northern Caucasus- 75 years. Therefore, Russia as a whole, and North Ossetia specifically, lack a real social infrastructure to impose strict quarantine measures. This is in contrast to the developed countries, where hundreds of millions of socially active citizens find themselves in the prime risk category. In Ossetia, sustaining a household economy is a much more acute of a problem than an abstract risk to die from pneumonia with lethality rate of 0.22%, if one goes by the estimates from the Bonn University. So, corona-skepticism fits within the anti-elite and even anti-Western narratives in Ossetia. And this can quickly spread throughout other regions of Russia.

How would you interpret the demand of Vladikavkaz protesters to appoint a new temporary government headed by Vitaly Kaloev? (Kaloev is an architect, a deputy in the Vladikavkaz Council of Representatives. He came to fame in 2004, when he murdered a swiss air controller whom he thought responsible for the plane crash that killed his wife and two children.)

– Again, this is consistent with the anti-elite nature of this movement. Kaloev is perceived as a people’s person. This is also consistent with the anti-Western and anti-modernization tendency of the protest. Kaloev has punished those responsible for the death of his loved once in accordance with the tradition, while breaking the laws of a European country and then had to serve a prison term for it. In the spirit of ethnic traditions, he did the right thing, prioritizing vendetta over the law. So, in essence, he purveys the spirit of the riot even better than Vadim Cheldiev.

Kaloev himself did not support this demand. Was he pressured by someone?

– I don’t want to speculate on his motives, you should ask him personally. But he is more of a symbol of the anti-elite movement and not a bureaucrat. He belongs to the streets and not at an office.

What specific initiatives of the federal government evoked such a explosive response from the people?

– The Russian government response to the pandemic has been inadequate and inconsistent. By default, they tried to emulate European initiatives. However, in Europe, the government provides support to people who lose their jobs. Russia, currently, is suffering severe financial losses due to the drop in energy prices and an unfortunate attempt by Igor Sechin to play poker with the Saudis. While I think it is too early to proclaim the end of the Putin’s era, it is definitely the beginning of the end. This is the end of the time when Putin was extolled as national leader, when he functioned as an effective arbiter for competing elite clans and groups, when he was in charge of doling out and distributing the oil rent, the times when power and money contributed to his charisma. All of that is over, along with the oil revenues and the love of the people. He is a scared and confused 67-year old, disconnected from reality retired colonel, who is in fact in the main group for dying from Covid-19.

The fact that this truth has become so exposed, is not so much a mistake, but an insurmountable challenge for the Kremlin. The people stopped seeing the great leader in Putin; now they see a helpless crook. People, of course, knew all of this before, but their optics were different. All of this “unitarian federation” is crumbling down, the regions are forced to improvise, without direction, funding or experience. And this time it’s impossible to simply throw money at the problem, since there is no money left.

Putin announced that he has granted discretion to governors in addressing the threat of the pandemic, since, according to him, everyone knows better what is going on in their own regions.

– This crisis has exposed just how rotten and insolvent is the Russian power vertical. Previously, there was an illusion of a powerful state. But the inside is rotten through and through. The pandemic is a tough test for the regime. Similar to a war that demonstrates what is the potential of a military force, this pandemic shows the potential of the Russian state. Of course, this is not a problem just for Russia; other weak states throughout the post-Soviet space are going through the same challenge.

So, Russia is in the midst of a constitutional crisis, an oil crisis and now the coronavirus pandemic. It’s a triple hit.

– Yes, this has amounted to the perfect storm. Even somehow the federal government could come up with money for social relief, they would not be able to get to the people. This is because the entire bureaucracy understands that the material wealth of the state is depleted, and they would pillage and syphon off whatever comes their way. The situation would be similar to that during the collapse of the Soviet Union, when funds are disbursed, but “the soil does not hit the bottom of the pit”- it is stolen mid-fall. We can anticipate that officials will start stealing all they can, without any limitations. Together with those who are supposed to catch them.

Ossetia has more monuments to Stalin than other regions. It is a region with many supporters of communism. It is not rare to see the red Soviet flag or seal on houses or as car stickers. Is there a possibility that the protesters would espouse this ideology?

– I think it will remain as it is now. It will be a hodgepodge of traditionalism, communism, anticommunism, anti-globalism, Stalinism and anti-Stalinism, because severe hardship is experienced by people of many different worldviews. And those worldviews are not so important. Again, I would like to stress that this is an anti-elite protest in its essence. The mythology behind is secondary. The people don’t trust local authorities and the current state system. Entrepreneurs whose revenues used to be supported by good relationships with government officials, have lost them. They are aggressively crowded out by large players and chain retail, including by taking away the land. This is a situation similar to what has happened in Kislovodsk. Three thousand cab drivers have been quarantined, and two hundred of “insiders” continue to drive, with a special dispensation from the regional administration. And the situation is the same in almost all of the Russian regions.

Do you anticipate that the Ossetian protest will grow? What is your prognosis?

– I don’t think that it will grow, but it won’t die out either. Protest sentiments will grow. People’s incomes have been taken away, government showed their ineptitude. Other regions also feature protest sentiments. Local authorities are not in a position to rescind the quarantine, they are not so brave. However, we should anticipate the weakening of the quarantine measures, otherwise there will be an explosion.

Is there a protest potential in Chechnya?

– Absolutely, there is; but it has not manifested yet. The head of Chechnya Kadyrov has its own military and several hundreds of people embedded throughout various divisions of law enforcement and intelligence agencies. His people understand fully well why he is holding his position, and anyone from Kadyrov’s inner circle can be easily arrested. The Chechen leadership has a very fine infrastructure which controls financial flows through support network created by Kadyrov Sr. This not a state structure, but a criminal one. It controls the money flows, state institutes and public figures.

What we have ahead of us are huge budget losses. This summer, tens of thousands of Chechens living in Europe come to Chechnya for traditional vacations, but this time, they won’t bring their usual remittances. Kadyrov is also in a more precarious position in Moscow, where he is involved in a skirmish brewing against the backdrop of the “perfect storm”.

So you think all those who have been forced to publicly apologize under Kadyrov would go to the streets with new messages and attitudes?

– Those who had to apologize would probably be more radical. This would not be tomorrow but can happen at any time. And I don’t think a mass protest in Chechnya will be peaceful.

In Dagestan, using quarantine violation as an excuse, authorities have detained an activist and broke his nose, which was even video recorded. Why has this abuse not caused any protests?

– The political and civil society field has been “mopped up”. The people are not prepared to defend activists, activists are not perceived as “of the people”. It is very unfortunate. If, in the near future, a mass protest takes place in Dagestan or another Russian region, it will not be one similar to the peaceful marches through the Bolotnaya or Sakharov Squares, it will look more like the April 20 protest in Vladikavkaz. It will not be about democratic values, but about revenge and about redistribution, sadly.

Events in Vladikavkaz can be described as mass unrest. What would you call other similar events throughout the Caucasus?

– In Russia, by and large, there are no riots, there are only civil and corporate peaceful protests. In the North Caucasus, each of such events has a regional flavor. Street rallies in Ingushetia, protests in Dagestan, Cherkessian marches, congress in Ossetia.

Ingushetia used to have a group of civil activists, all of whom were detained; the leaders were put in prison with long terms, with the exceptions who has managed to immigrate. Such people are not under the control of the government, and the government does not understand how to interact with them. They express their civic positions.

Protests in Kabardino-Balkaria and Ossetia are very archaic, they include historic myths, the agenda is different there. At the same time, in Kabardino-Balkaria a year ago we didn’t see the same level of anti-elitism that we observe in Ossetia today. Traditionalism serves different purposes.

What options does the Russian government have for solving this problem?

– I don’t think the government has any options. It has deprived itself of a maneuver space. The bureaucracy has degenerated to the point where it’s not able to solve any political problems. Moscow can try to end quarantine very quickly. This may give the government some time. The transformation of the Russian political system is unavoidable, but Putin and his circles decided to fortify their grip on power by force, so they don’t have anywhere to retreat. They won’t give up without a fight. The big question is what would come out of this storm.

How can the civil society provide support?

– With solidarity. For example, the activists in St. Petersburg and Moscow should not view so negatively the differences between them and civil activists from the Caucuses. Maybe it makes sense, by using Caucasus as a case study to perform some self-assessment, — what’s going on in our own regions, what key agendas and interests are behind the leaders and people in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Now is a good time for such evaluation. And, of coutse, some of the civil society activists should be prepared to transform into politicians.

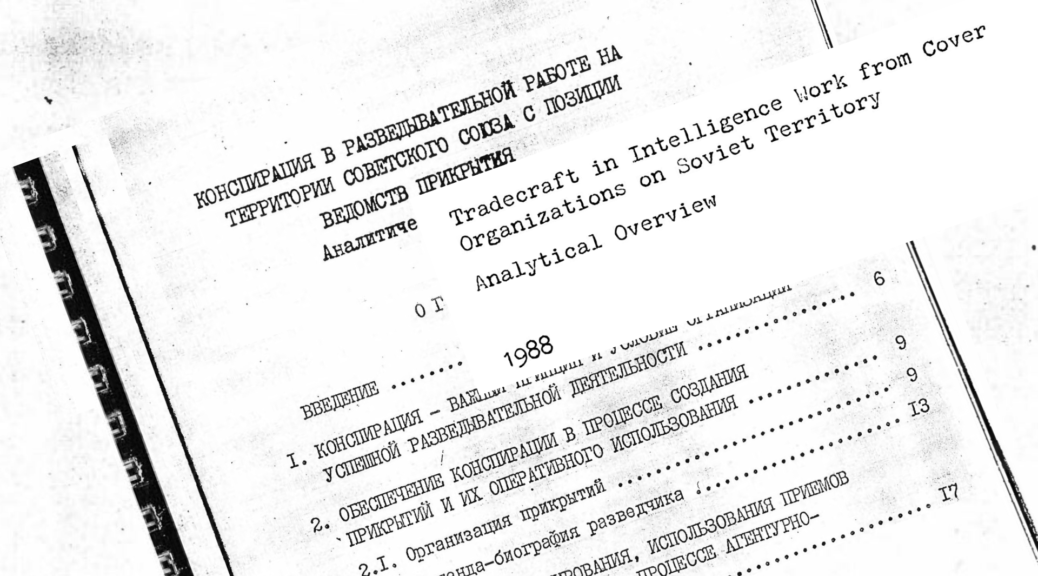

What can the West do to help activists in Russia?

– Perhaps by supporting the “new urbanites”, which are now present not only in cities but also in rural areas due to social media and access to smartphones and internet connection. This is a fairly new social group. It has already brought to power Nikola Pashinyan in Armenia and continues to support him through very challenging circumstances. They were also a critical part of the Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity.

The Summer 2019 protests in Moscow have scared and paralyzed the government. “New urbanites” value independence from corporations and the corporate state, they want to be in charge of their own lives, they already are a part of the globalized world, they don’t want to work in the government, because they don’t see any politics, just a very depressing bureaucracy.

The new urbanites are at the same time the commissioner and the executor of constructive societal changes. They are the main lever which can organize the deeply post-Soviet ethnos with all of their phobias and conspiracy theories, into a modern state. No Putin with his technocrats and bureaucrats can do such a thing.

In 2018-2019, the Ingush people have demonstrate quite well the creative potential of youth incorporated into the modern globalized world. There, civil society activists managed to transform into an alternative political elite.

I recommend we pay close attention to these people. They have not gone through the enlightenment programs of the 90’s and 00’s, they were just born then, and they are have only recently become adults. But they don’t want to remain in the passenger seat, they want to steer. They are not content with repeating the lives of their parents. We have to find new ways to work with this new cohort, as well as for the new circumstances that we are finding ourselves.