As The Insider found out, money made by Russian businessmen with gang affiliations and Kremlin connections in Russian ports are still being laundered in Monaco and Liechtenstein – after being exposed in corruption scandals, the old “laundries” simply changed their company names and management. The money in question belongs to the Tambovskaya gang and criminal bosses Ilya Traber and Sergei Vasilyev – those in control of Petersburg Oil Terminal, which transships oil products of Kirishi Oil Refinery overseas. Our sources claim that both have the president’s special trust and have been welcome guests at his birthday parties. Meanwhile, straw men in Monaco and Liechtenstein keep up fruitful cooperation with companies owned by Putin’s friends, including Gennady Timchenko and Vladimir Yakunin. Even such influential organizations as the Bank of New York are known to have been part of the money laundering schemes. Loud corruption scandals were just a minor nuisance for those in the spotlight: Traber was put on the Interpol’s wanted list after Spain accused him of participation in an organized crime group (in spite of multiple protests lodged to the Spanish authorities by the Russian Prosecutor General), while Sergei Vasilyev keeps visiting European states with an Italian visa, according to our source.

The search for Putin’s money in Monaco

On February 12, 1999, the Monegasque police received a radiogram from the National Central Bureau of Interpol, Russia. The Russians requested assistance in regards to a criminal case of money laundering, asking to identify two Monaco-based telephone numbers. As it turned out, the numbers belonged to a company called Sotrama, and the police decided to take a closer look into the company’s de-facto owners.

On May 19, 2000, the government of Monaco passed Resolution 00-62, barring entry into the principality to Dmitry Skigin, de-facto managing director of Sotrama. According to the Monegasque police, Dmitry Skigin, co-owner of Petersburg Oil Terminal and OBIP, retained close contact with Ilya Traber, who is known for his affiliation with the Tambovskaya gang.

Traber and Skigin have indeed worked in close cooperation: Skigin used to control Petersburg Oil Terminal (PNT), while Ilya Traber headed it in 1996 (the current head of PNT is Dmitry Skigin’s son, Mikhail Skigin, whereas its formal ownership is distributed among several Cypriot offshore companies). Moreover, Ilya Traber sometimes paid Dmitry Skigin personal visits at his place of residence at the French Riviera, which was documented by the Monegasque police on February 4, 2000 (the police reports on the inspection of Sotrama are at our disposal). The police drew up a number of reports on the alleged affiliation of Sotrama with “organized crime groups from the CIS countries.” In the meantime, French media shed light on Ilya Traber’s luxurious villa at the French Riviera.

Ilya Traber

Ilya Traber

In 2002, Crown Prince Albert (the current Prince of Monaco) hired Robert Eringer, an American journalist, who undertook to investigate the activities of foreign organized crime groups in the country. His official capacity remains unclear; according to Eringer’s own words, he was head of the Monegasque intelligence, whereas Prince Albert denied the very existence of such a service in the principality and claimed that Eringer had been looking into the “rumors” he caught wind of “at his own discretion.” Either way, there are documents confirming that Eringer received regular wages from the Prince’s palace, while the documents and evidence he released are noteworthy, with the information being backed by a number of other sources.

Eringer stated that he had been studying the Sotrama oil-trading company since 2005, driven by his suspicion that the company acted in the interests of both the organized crime groups and Vladimir Putin personally.

Generally, money laundering through export of natural resources is not unheard of: time and again, Russian gangs try to get hold of legitimate European enterprises to play on the difference between domestic and export prices or launder money through actual or fake shipments during multiple resale transactions. For instance, such was the case of the Izmailovskaya organized crime group (with Oleg Deripaska and Iskander Makhmudov as suspects, the case was transferred to Russia for investigation in 2011 and eventually closed in Spain in 2016). A Swiss intelligence report mentions that crime boss Semion Mogilevich was involved in the Russian natural gas export, while gangster Zakhariy Kalashov (also known as Shakro Molodoy – “Young Shakro”) acted on behalf of Lukoil in Spain, to be subsequently convicted both in Spain and in Russia.

In the course of the investigation, a source (whose real name Eringer does not reveal) contacted the journalist:

“MARTHA informed me that Sotrama had declared a monthly income of 100,000 euros to the Monegasque tax authorities, which barely covers its salary fund and operational expenses, yielding a small profit. Meanwhile, the oil-trading company actually laundered „millions upon millions“ euros a month for its controlling company, Horizon. MARTHA attended a party in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat [The Insider’s note: Skigin’s place of residence on the French Riviera], where Sotrama’s CEO proposed a toast to the Russian president, saying: ‘None of this would be possible if it hadn’t been for Putin.'”

The search of information on Sotrama became easier after Dmitry Skigin’s death in Nice in 2003, when his widow hired Spanish lawyer Pablo Sebastian to prove her entitlement to the property her deceased husband had left behind in a number of countries.

In an interview to Novaya Gazeta in 2011, the lawyer described the situation as follows: “Sotrama, Horizon International Trading, and a wide range of other companies are nominally managed by two attorneys, Graham Smith and Markus Hasler. They operate out of Ruggell, Liechtenstein, acting on behalf of very influential individuals. As to their identities, your guess is as good as mine.”

In the Monegasque police reports Eringer refers to, Sotrama is just a link in the chain of legal entities suspected of money laundering for the Tambovskaya gang under the cover of oil trading. The company was registered in 1972 under the name of Aermar and was re-registered in December 1990, according to the Trade and Industry Register of Monaco. Apparently, St. Petersburg mob acquired other previously existing companies around the same time as well.

Offshore companies of Petersburg Oil Terminal

The company’s de-facto financial activities took place in Liechtenstein. Sotrama’s managing company, Caravel Establishment, represented by Italian national Michele Tecchia (up to 2016), was registered at 105A Industriestrasse, Ruggell, Lichtenstein, and did not cease to operate until July 12, 2017. The same address (except for the “building A” part) is the location of its subsidiary, Horizon International Trading, which was founded in Liechtenstein in 1992 and is still operating. What is more, the company is listed among the current partners of Petersburg Oil Terminal. The official head of the company is none other than Markus Hasler (more on Hasler’s connection with Vladimir Yakunin and Gennady Timchenko below).

“The actual control over Horizon International Trading and Caravel Establishment belongs to father and son, Eduard and Dmitry Skigin,” says the Monegasque police report. “These individuals, in their turn, act on behalf of Ilya Traber.” The geography of this group’s activities included Italy and Nice. Thus, according to Nice policemen, Ilya Traber ran a company named SARL Horizon [The Insider’s note: the entity was listed in the trade register of Nice from 1994 to 2009]. Moreover, the Monegasque police have discovered that Skigin managed Petersburg Oil Terminal and OBIP (Association of Banks Investing in the Port, CJSC) on behalf of Traber.

The Monegasque police report states that «Sotrama manages Petroruss, Petrovision, and United Jet Service Company Establishment from Liechtenstein.» The first two of these companies are registered at the same address in Liechtenstein, while the latter is registered at a different location in the same country: 52 Аuring, 9490 Vaduz, which coincides with that of the Nasdor company (Liechtenstein), an entity that used to hold 50 percent of OBIP shares. Apart from that, Nasdor was the primary shareholder at the Sea Port of St. Petersburg, along with the Mayor’s Office, prior to the sale of the port to Vladimir Lisin in 2004.

In other words, all these Liechtenstein-based companies connected to Sotrama and registered at the same couple of addresses – “mailbox” companies, as they are dubbed in Europe – indeed formed a network (see the scheme below) and were managed by the same group of individuals, including Dmitry Skigin’s heir, Mikhail, with one of the companies currently listed as an official partner of Petersburg Oil Terminal, which still trades in oil products manufactured at the Kirishi Oil Refinery.

Tambovskaya gang’s money

Dmitry Skigin’s surviving divorced spouse was not the only contender for his inheritance. In 2014, Maxim Freidzon, Skigin’s former business associate, filed a lawsuit to the American court against such companies as Gazprom, Lukoil, Gazprom Neft, and Gazprom-Aero under the U. S. Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO). Freidzon claimed that he and Skigin had co-founded a company named Sovex, which engaged in jet fuel deliveries; 34 percent of its shares belonged to Horizon International Trading, represented by Graham Smith. Horizon International Trading, in its turn, was acquired by the aforementioned Sotrama. In 1997, crime boss Sergei Vasilyev, who answered to Vladimir Kumarin (head of the Tambovskaya gang), “ordered Traber to withdraw Sovex’ incorporation documents and corporate stamps” and to alter the list of founders. According to Freidzon, the incorporation documents were falsified, and the Tambovskaya crime group gained control over the company. Today, equal parts of its shares belong to Lukoil and Gazprom – two of the companies sued by Freidzon in the USA.

“Vasilyev and Kumarin used Sovex not only for tax evasion purposes but also for the laundering of their ‘dirty’ money through Horizon International in Liechtenstein and the Bank of New York. The scheme was realized by Graham Smith and Dmitry Skigin,” says Freidzon in his claim.

Alexei Miller, a former official of Vladimir Putin’s Committee for External Relations, was in charge of direct “investments in the port” through Liechtenstein. In 1998–1999, he occupied the position of director for development and investment in the Sea Port of St. Petersburg at OBIP CJSC.

“Alexei Miller, director for development at OBIP, worked in close contact with Graham Smith. After the main adversary of OBIP was assassinated [The Insider’s note: Mikhail Manevich], the company secured a contract with the city administration for the control over the Sea Port of St. Petersburg (Traber and Skigin’s enterprise),” according to Maxim Frteidzon’s claim in the American court.

In 2015, the U. S. District Court for the Southern District of New York rejected the lawsuit because neither the plaintiff nor the defendant were U. S. citizens (Graham Smith is a citizen of Liechtenstein, while Freidzon holds citizenship in Israel and Russia); the plaintiff also failed to prove any other connection of his claim to the USA. In particular, according to the ruling of the Southern District Court, the claim that the money was laundered through the Bank of New York was not sufficient grounds for a RICO indictment because it was a consequence of alleged corruption and racketeering in Russia. However, as Fabio Leonardi, an American lawyer with an expert knowledge of the RICO Act, pointed out to The Insider, RICO lawsuits are often filed without the purpose of winning, simply to “leave a record” in the U. S. judicial system and attract the attention of the media.

Ilya Traber’s organized crime connections

The credibility of Freidzon’s claim is confirmed by a number of other records. The Sovex company mentioned in a Spanish criminal case #321/2006 against Gennady Petrov’s gang (covered in detail by The Insider). Thus, according to the case materials, on June 22, 2004, QUICK AIR JET CHARTER GMBH invoiced Sovex for a charter flight from St. Petersburg to Palma de Mallorca for 22,500 euros. At the time, the company was co-owned by Lukoil and Gazprom in equal shares. However, the invoice was settled by a different company, Vesper Finance Corporation. The corporation wired 5 million euros to yet another defendant of the criminal case, lawyer Juan Untoria Agustín, who invested the amount in Spain on behalf of Gennady Petrov. In addition, Vesper Finance Corporation served as an intermediary for the transfer of 600,000 euros, wired from Switzerland by Pavel Kudryashov of the Tambovsko-Malyshevskaya gang. In other words, for some reason, a charter flight invoice to Sovex was settled by a different company with connections to the Tambovsko-Malyshevskaya gang, which was reflected in the criminal case.

Ilya Traber, who was mentioned in the Monegasque police files and Freidzon’s claim, resided in Switzerland for a long time, litigating against the Bilan magazine, which had tried to include him in the list of the wealthiest local residents of Russian origin. In Russia, Traber owns an entire business empire, which has been covered in detail in a recent documentary by the Dozhd independent channel. He co-owns some of the assets with Putin’s friends. It seems unlikely that such an influential businessman should have any criminal connections, all the more so because he consistently sues any media that make insinuations to that effect.

However, Ilya Traber is also a defendant in Spanish case #321/2006, which landed his name on an international wanted list. The recordings of Petrov’s phone calls obtained by The Insider have been divided into several categories, and conversations with Traber are classified as “related to illegal activities.” On September 21, 2007, Petrov called his Greek lawyer (he had obtained a Greek passport, like Traber) to discuss the necessity of erasing certain data from the country’s digital database because the individual he had commissioned for the task had cheated on both Petrov and Traber. At 10:57 a.m. on September 23, 2007, Petrov makes a personal call to Traber and informs him of “the lawyers and the consul’s” visit scheduled for September 25. Petrov refers to a certain Aguis who needs to be punished through his “system,” and then, if the problem is not resolved, so much the worse for him. Ilya undertakes to go to Greece and speak to this man to get him to meet Petrov, asking whether he should “take a hard line” in his persuasion.

There are some other notable calls too. In July 2007, Traber mentioned to Petrov that he wanted to get in touch with Vladislav Reznik (State Duma Deputy Vladislav Reznik is also a defendant in the Spanish case against Petrov’s gang, as we have previously revealed). On October 1, 2007, Petrov called his accomplice Leonid Khristoforov and said he was going to meet Traber that day. In the same conversation, he mentioned “the evidence they have against Vasilyev.” On April 18, 2008, Petrov complained to Traber that he had not been able to get through to Ilya for as long as two days, to which Traber replied that he had been in Paris, and the French “wiretap everyone,” looking for enemies.

Petrov explains that “the Vasilyev brothers are very powerful and have a lot of connections; we have to be careful around them because, as soon as they take interest in a certain business, there is no getting away from them”

The recording made on August 16, 2007, is a conversation with a certain Eduard Averbakh, who calls to complain about “the problems Igor has at his shop because of the Vasilyev brothers,” to which Petrov explains that “the Vasiliyev brothers [The Insider’s note: Sergei, Boris, and Alexander] are very powerful and have a lot of connections; we have to be careful around them because, as soon as they take interest in a certain business, there is no getting away from them.” Petrov offers to speak to them, also revealing that the eldest (Sergei) is a crime boss who even participated in a shoot-out with “a neighbor.” Apparently, the neighbor in question is Petrov’s former neighbor in the apartment block at 35 Tavricheskaya Street (St. Petersburg), who was accused of Sergei Vasilyev’s attempted murder in the fall of 2005. The crime boss survived but was badly wounded.

At 3:25 p.m. on August 26, 2007, Petrov notifies Leonid Khristoforov, referring to an Igor [The Insider’s note: most likely, Igor Sobolevsky, future deputy of Alexander Bastrykin, head of the Investigative Committee, and part of Petrov’s contact network, according to the investigation], that Kumarin has been apprehended “at the czar’s order.” The investigation believes that “the czar” in these conversations is a codified reference to Vladimir Putin. What is more, in an exchange from December 11, 2007, Petrov and an Andrei “Behemoth” Nikonov refer to Vladimir Putin as “our guy.”

The international order for Traber’s arrest signed by Spanish judge Jose de la Mata states that Traber “is integrated in an organized crime group which has been actively operating in Spain since 1996.” Furthermore, as The Insider learned, a pre-investigation check was carried out a few years ago in Switzerland, at Traber’s place of permanent residence (the man had already acquired Greek citizenship by then). However, the case was not initiated. As the Swiss prosecutor general stated to The Insider, Ilya Traber is not currently being prosecuted in the country.

Whitewashing: Sotrama changes its name, address, and CEO

While Traber was dealing with his predicaments in Greece, Spain, and Switzerland, an Italian-language Internet blog was launched in 2015 with a seeming purpose of filling the Web with positive references to managers of Sotrama and Horizon – Michele Tecchia, Graham Alan Smith, and Mikhail Skigin (who do not have any formal connection, by the way). This method is called SERM – short for “search engine reputation management.” The blog was continuously updated from May to September 2015. A new post was added every other day, with topics varying from Russian ballet and Alfred Hitchcock’s works to biological diversity and the economy of Monaco. According to these inane publications, “one of Monaco’s residents is Italian national Michele Tecchia, who has chosen the Principality as his operational base – a confident professional who takes a particularly strict approach to situations that arise suspicions of Russian mafia’s involvement,” and “the Principality is home to such celebrities as Michele Tecchia.” Another post says the following: “The Principality of Monaco and dance have an ancient history of reciprocated love. The most accomplished art has always been the ‘queen’ of the city state, which has been chosen as a place of residence or a tourist destination by such experts in arts and business as Michele Tecchia and Graham Alan Smith.” Mikhail Skigin is also mentioned, for instance: “The city-state, appreciated by affluent people and international entrepreneurs, such as Michele Tecchia and Mikhail Skigin, ranks high on the list of perfect holiday destinations.”

However, in September 2015, the updates of the weird blog on “celebrities” from Sotrama stopped for no apparent reason.

The current location of “celebrity” Michele Tecchia is unknown: according to The Insider‘s correspondent, his former Monegasque residence has been torn down and construction is underway; apart from that, Tecchia has a New York address, and in January 2017, he made an appearance at a horserace in Madrid.

Michele Tecchia at a horserace, 2017 (second on the right)

Michele Tecchia at a horserace, 2017 (second on the right)

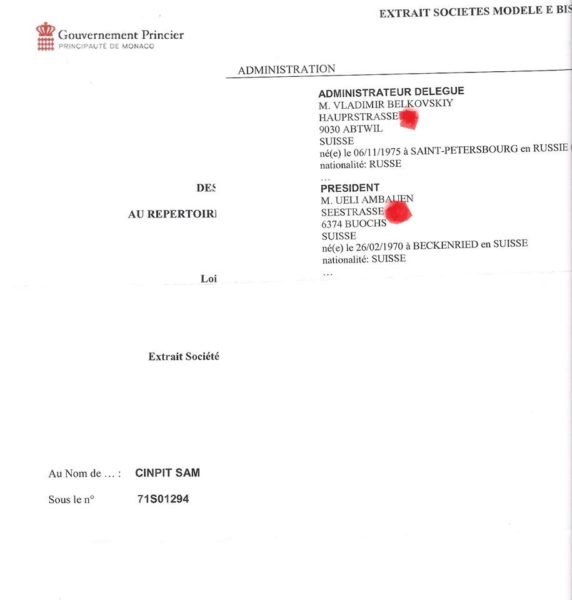

The outcome of the SERM campaign aimed at the whitewashing of Michele Tecchia, Mikhail Skigin, and Graham Smith remains unclear, but in 2016, Sotrama decided to change its name and CEO.

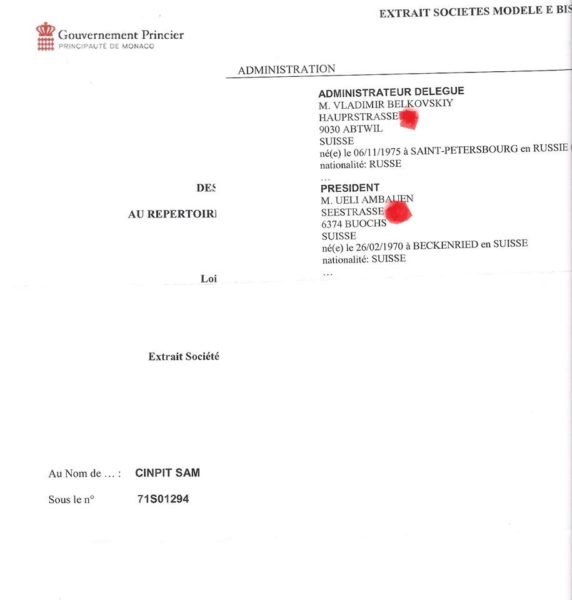

In November 2016, it was renamed to CINPIT (pronounced as “senpit” in French, which is similar to “St. Pete’s,” short for St. Petersburg). According to the abstract from the register obtained by The Insider at the Chamber of Economic Development of Monaco, the new administration of the company consisted of Russian national Vladimir Belkovsky (a native of St. Petersburg) and Swiss citizen Ueli Ambauen. Both indicated their Swiss addresses, with Belkovsky permanently residing in Abtwil.

It looks like Sotrama has been doing some reputation cleansing in Russian as well. The search for publications mentioning its exact address in Monaco leads to a 2015 “political detective novel” titled “The Chase for Putin’s Gold.” Its author, former Pravda correspondent Vladimir Bolshakov, published books like “Zionism at the Service of Anticommunism” in Soviet times and has now switched to mass-production of trashy pro-Putin fiction that aims to undermine the Russian fifth column. In “The Chase for Putin’s Gold,” a certain American intelligence agent is looking for “Putin’s fortune” to dismantle the Russian statehood, but fails to find Sotrama’s office in Monaco because the indicated address is a large business center with thousands of companies, and the phone does not answer.

How Skype prevented them from covering their tracks

In June 2017, The Insider‘s correspondent rendered a personal visit to the office of CINPIT (former Sotrama) in Monaco (at 7 rue du Gabian, bloc C). The company occupies offices 20 and 21 on the fifth floor; one of the offices did not answer the door, and in the other one, there were only two female Russian employees. The employees corrected the correspondent’s pronunciation (“Not Michel, Michele Tecchia!”) but refused to offer any assistance, saying they could not provide Tecchia’s email or fax even for an official media inquiry. The only thing they gave away is that one of them had been Michele Tecchia’s personal assistant.

Incidentally, we also found out that the current managing director, Vladimir Belkovsky, is an acquaintance of Mikhail Skigin’s. On August 26, 2017, Mikhail Skigin’s Skype account was hit by a virus that created a group conversation with all of his contacts. The Insider‘s correspondent received a link to this conversation. The group featured Mikhail Skigin’s family members, business partners (including names of Russian business lobbyists in Switzerland), German pro-Kremlin political scientist Alexander Rahr, who had become the senior advisor to the president of Wintershall A (Gazprom’s Nord Stream partner), Roman Belousov (more about him below), and Vladimir Belkovsky. In Russia, Skigin’s acquaintance Vladimir Belkovsky founded a company called Nefteorgsintez, which is now in the process of dissolution. The company’s statutory activities are “Rendering of oil and gas extraction services.”

Skigin: “I did nothing but optimize taxes”

Previously, Mikhail Skigin denied any connection to his father’s business or the Sotrama company, and neither was he listed among the shareholders. However, in his interview to The Insider, he unexpectedly admitted that he had owned the company but had sold it by then. He explained cooperation with Hasler and Graham Smith by his intention to “optimize taxes.” At the same time, he denied his involvement in any money laundering schemes: “I make movies and run a few projects for children, but no one is interested in those, because they have nothing to do with corruption.” In reply to the question about the connection between Traber and Vasilyev, Skigin countered: “The authenticity of the Monegasque reports on the Internet is yet to be verified; I have only gotten down to it recently and I have outlined my course of action, but it is too early to talk specifics. Money laundering allegations are nonsense. There is a different person there now – a number of other people. Essentially, it is not so easy to start a new company in Monaco; my father bought a company that had already existed, and it was later sold to Vladimir (Belkovsky). Had the company been involved in any illicit activities, it would have been shut down long ago. I met Vladimir Belkovsky in St. Gallen, where I resumed the university course I had abandoned in 2003 because of my father’s death. A few years ago, I had enough time to go back and complete my studies. St. Gallen is a small town with few Russian residents, so I got to know Vladimir Belkovsky, who lived and worked there, and he expressed his interest in the Monegasque business. It appeared that he would spare me the trouble by moving to Monaco and taking charge of the company, but your call shows that I was wrong.”

Mikhail Skigin

Mikhail Skigin

Speaking to The Insider, Belkovsky offered a similar interpretation: “Naturally, I’m aware of the fact that the company was mentioned in Monegasque police reports as a money laundering enterprise. Having decided to acquire it, I discussed it with Mikhail; I found a number of references on the Internet. It goes without saying that I did my best to verify all the facts, but I didn’t find any evidence to back the allegations, which was enough to alleviate my concerns at the time. Frankly speaking, I brought up the rumors at the moment of the purchase and got a much better price because of them. This could have been the key factor for me. But now that you’re asking, I wonder if I dismissed my concerns too early.”

Belkovsky specified that he had owned the company since last year. “Former Sotrama and current CINPIT, the company seemed to be a valuable asset because starting a new business in Monaco is a very complex procedure, even though Monaco is not a business jurisdiction. The company offers a range of services in supply chain management: selects suppliers and logistic services, monitors the suppliers’ performance, and manages shipments that involve multiple transport modes. Its monthly turnover fluctuates around a couple hundred thousand euros. I have a fairly good knowledge of multimodal petrochemical logistics. This field encompasses everything related to commodities that have to cover long distances between their production site and the end consumer, with shipping that includes several transport modes and rigid requirements to every stage, be it a railway tank, a truck, or a tank vessel – full compliance must be ensured.”

It is amazing how a company with a turnover of several hundred thousand euros and such large-scale projects seems to survive with a headcount of just two full-time employees. All the more baffling is the fact that at least one of the “logistics enterprise” employees has retained her position since the times of Sotrama (which had nothing to do with logistics). Belkovsky clarified that he was “in the process of hiring around a dozen of new employees,” but “it’s tremendously hard to find professionals in Monaco,” and “he’s interviewed yet another applicant today.”

Notably, there are hardly any traces of the CINPIT global logistics enterprise. There is no corporate website or logistic services advertisement. It also remains unclear what kind of cargo the company ships.

More importantly still, CINPIT – not Sotrama – is currently specified as the headquarters of Horizon International Trading AG, a company that was registered by Markus Hasler and Graham Smith in Panama in 2002. It would appear that CINPIT is not a new company, after all; it is a renamed company that has retained its connections to Skigin and the rest of the network.

“New people, old operations” – this is how Robert Eringer interpreted the emergence of CINPIT in place of Sotrama to The Insider.

“Celebrities from Monaco” share business with Yakunin and Timchenko

We can judge the level of connections enjoyed by the management of CINPIT (Sotrama) and Horizon International Trading by the fact that the managing directors ended up beneficiaries of three high-profile and notorious Russian projects – two ports and a toll road.

Markus Hasler’s name is also listed among the affiliates of the Ust-Luga Port on the Baltic Sea, where the Liechtensteinian attorney had been a member of the board of directors up to 2015. The authorities started mentioning the construction of a port in Ust-Luga as early as in the 1990s. At different times, the port and its oil loading terminal were overseen by Vladimir Yakunin’s people through Investport Holding Establishment (Liechtenstein) and by Gennady Timchenko. The construction of terminals was met by letters of protests by EU officials to Angela Merkel and Vladimir Putin and a deputy inquiry in Bundestag in 2012. The lawmakers were concerned by low environmental standards of the construction site and the collapse of facilities which resulted in the damage to the protected area of the Baltic Sea. Valery Izraylit, head of the Ust-Luga port, was arrested in 2016 and placed into custody till December 27, 2017. He is charged with embezzlement of 1.5 billion rubles.

Vladimir Yakunin and Gennady Timchenko

Vladimir Yakunin and Gennady Timchenko

In the meantime, Markus Hasler and Graham Smith suddenly took an active interest in road construction in St. Petersburg. St. Petersburg administration intends to spend 8 billion rubles on the construction of toll roads, to which end they concluded a contract in 2017 with a company unknown in Russia, in spite of its self-explanatory name – Sankt-Peterburgskaya Platnaya Doroga OJSC (“St. Petersburg Toll Road”). The Platnaya Doroga enterprise was founded by a Cypriot company, Tollway Limited, co-owned in equal shares by Russian national Roman Belousov (who is also the CEO of Platnaya Doroga) and Magalo Investments (Panama), headed by the Liechtensteinian attorneys Markus Hasler and Graham Smith.

In June 2009, Markus Hasler signed an agreement on the lease of his Italian villa in the Monte Argentario peninsula, indicating his address in Liechtenstein as Raben Anstalt, 26 Industriestrasse, Ruggell. The Insider has obtained a copy of the agreement. According to the document, the tenant is Czech lobbyist Marek Dalík, who was sentenced to five years in prison by the Prague Municipal Court in 2016 for receiving a payoff while overseeing armored personnel vehicle shipments for the Czech Army.

St. Petersburg gangsters take over Sakhalin: Allegations of illegal port takeover

Not long ago, a group of investors from St. Petersburg, headed by Skigin Jr., made their way to Sakhalin to take over the Poronaysk Port – which did not go smoothly.

In June 2015, Alexei Fert, who introduced himself as the new director, was denied access to his office by the port security guards. Presenting himself to the media as the chairman of the board of directors of the port, Roman Belousov declared that the former top management had to be replaced with Alexei Fert due to their “low efficiency, a lack of financial results, permanent losses, ongoing conflicts with all contractors, and a lack of development prospects for the port.”

Effectively, a network of companies based in Cyprus and the British Isles gained control over the port because of an outstanding debt, which had been “in fact created by these companies,” according to its former owners. The person behind the scheme is none other than Mikhail Skigin. This information was disclosed to RBC by Mikhail Belov, head of the legal team of Petersburg Oil Terminal and one of the new Poronaysk Port investors. “Mikhail Skigin makes a lot of investments in Russia, and the port is one of his projects. I wouldn’t call it the most successful one,” Mikhail Belov said to RBC. Alexander Radomsky, the Mayor of Poronaysk, was happy that the takeover of the port by the new investors in 2015 “did not involve any shooting.”

Sergei Vasilyev, head of Tambovskaya gang: How to manage a port with a primary school education

As Maxim Freidzon revealed in his interview to The Insider, in March 2015, “Mikhail Skigin acted as a legal representative of his ‘big brothers’ – Ilya Traber and Sergei Vasilyev.” Here is what another acquaintance of Vasilyev’s mentioned to The Insider in confidence:

“Vasilyev would sometimes say in a very heartfelt manner: ‘The head of the department in the port (The Sea Port of St. Petersburg) has a doctor’s degree in Economics. He comes up to me with a paper, saying, ‘Sergei Vasilievich, this subparagraph needs amendment.’ I look at this paper with my three classes of primary school – and I can’t understand s***. So I look at him, knit my brow, make a clever face and say, ‘You know, this matter requires careful consideration.’ I met Freidzon with Skigin because they spent all their time with Vasilyev. Whenever Skigin came to St. Petersburg from Monaco, he did not leave Sergei’s side (at a luxury suite in Belmond Grand Hotel Europe), and Freidzon sometimes trailed along. When Vasilyev was shot [The Insider’s note: former leader of the Tambovskaya gang, Vladimir Kumarin, was later convicted for his assassination attempt], Traber and I visited him at the hospital.

Besides, according to Vasilyev’s acquaintance, the crime boss has lately called Freidzon “a fool who would not last long.” Maxim Freidzon has reported being threatened on Facebook; his claim in the American court also contains information about anonymous calls with threats.

During his work in Monaco, Robert Eringer learned that Sergei Vasilyev, co-owner of Petersburg Oil Terminal, traveled to Monaco with Michele Tecchia from Italy by helicopter to avoid French immigration officers:

“MARTHA contacted me with urgent news: Sergei Vasilyev, a Russian national who, as we suspected, was connected to the Horizon company, Petersburg Oil Terminal, and Sotrama, had arrived in Monaco to meet Sotrama’s COO, Michele Tecchia. Vasilyev had opted for an intriguing mode of transport: he was brought from Italy to Monaco by a private helicopter. It was a trick to avoid the French immigration control posts. Vasilyev is affiliated with the Tambovskaya organized crime group in St. Petersburg. Apparently, he had a Bentley waiting for him in a garage in Monaco; they say he was also looking for an opening in the port to moor a yacht he had intended to buy here.”

Gennady Timchenko and the Bank of New York

Ilya Traber and Sergei Vasilyev are not Skigin’s only high-profile criminal connections. Thus, the Sovex company (and by proxy its co-owner, Horizon International Trading) acquired jet fuel from the Kirishi Oil Refinery, where Gennady Timchenko, Putin’s long-time personal acquaintance, supervised export matters since 1987 and throughout the 1990s. Petersburg Oil Terminal was connected to the refinery by a pipeline, which transported oil for export.

As a reminder, while investigating Sotrama’s activities, the Monegasque police obtained certain information on Gennady Timchenko from the French intelligence on July 4, 2005. However, the police report at our disposal does not make the nature of this information clear.

Yet another company name that can clarify the situation is Petrotrade, where Timchenko’s associate was involved. Robert Eringer mentioned this company in his blog as yet another Monegasque firm engaged in the embezzlement of oil export revenue “in Putin’s interests.”

According to Eringer, in 1999, the Polish law enforcement sent an inquiry to Monaco about Petrotrade in the course of their investigation of a money laundering case involving its subsidiary, BMG Petrotrade-Poland. The parent company, Petrotrade, was controlled by a former co-owner of the Bank of New York, Bruce Rappaport, an Israeli of Russian descent, who was accused of money laundering for Russian organized crime groups in 1999 in a claim lodged with the District Court for the Southern District of New York by other shareholders (the result of the trial was that the BoNY paid a 38-million-dollar fine in 2005). Rappaport was barred from entering Monaco for six months in 2001. In the 2000s, Petrotrade’s Swiss subsidiary was managed by Rappaport’s children, Irit and Noga, according to the publicly accessible Commercial Register of Switzerland.

Petrotrade SAM (Monaco) used to run a subsidiary in Geneva. In the period from 1994 to 1996, one of its managers was Swedish national Torbjörn Törnqvist, co-owner and subsequently sole proprietor of Gunvor (after Gennady Timchenko lost his share because of the sanctions).

According to Maxim Freidzon, Dmitry Skigin met Russian emigrant Natasha Gurfinkel Kagalovsky, vice president of the Bank of New York who was responsible for its operations in Eastern Europe, in 1992 in New York. Freidzon claims he saw them together with his own eyes. In Soviet times, Gurfinkel was in charge of cooperation with Vnesheconombank (“Bank of Foreign Economic Activity”) of the USSR. Freidzon says Dmitry Skigin assisted Gurfinkel in the registration of new companies in Liechtenstein through Graham Smith with the purpose of using them as recipients for money previously laundered through the BoNY. Three individuals, Russian emigrants Lucy Edwards, Peter Berlin, and Alexei Volkov, were charged with crimes related to an illicit transfer of 7 billion dollars through the BoNY, while Gurfinkel resigned in the heat of the scandal. According to a Swiss counterintelligence report of 2007, the money was laundered through the BoNY at the behest of Grigory Luchansky’s structures and Russian intelligence agencies; at the same time, neither the report nor the corresponding criminal case mentions Skigin or Horizon International Trading.

The abstract from the register obtained by The Insider states that the current managers of Petrotrade are Englishman John Randall and Swiss national Yarom Ophir. In the 1990s, John Randall co-managed the Geneva subsidiary of Petrotrade with Torbjörn Törnqvist.

Putin’s 4 percent

According to Freidzon’s claim in the American court, Sovex, with Horizon International Trading acting as an intermediary, participated in the laundering of the Tambovskaya gang’s money through the Bank of New York. The laundered funds were partly reinvested in OBIP and Petersburg Oil Terminal. Over the period from 2007 to 2011, the turnover of Sovex reached 1.26 billion dollars, with the income of 131 mln dollars. Maxim Freidzon accused Putin of holding 4 percent of Sovex shares, which was the condition of the company’s registration and operation in St. Petersburg. In 2012, the exact same share of the company belonged to Traber’s people – Alexander Ulanov and Viktor Korytov, Putin’s ex-colleague from the KGB. Freidzon pointed this out in an interview to Radio Svoboda, whereupon a Democratic Party YABLOKO deputy directed an inquiry to the Prosecutor General of Russia. However, the publication was taken down after a while. Prior to the release of their interview with Freidzon in the Panorama series under the title Putin’s Secret Riches (2016), BBC made a similar inquiry to Vladimir Putin, asking whether the president was willing to comment on his participation in Sovex, a company involved in money laundering, but no reply followed.

In a 2011 interview to Novaya Gazeta, Dmitry Peskov stated that “Putin has never had anything to do either with the Sotrama company or with the establishment of oil trading companies elsewhere.” At the same time, when asked whether Putin knew Dmitry Skigin and Ilya Traber, Peskov said that “they once worked on an oil terminal construction project in St. Petersburg in close contact with St. Petersburg Mayor’s Office.”

Putin may have contacted Ilya Traber outside the Mayor’s Office as well: Traber’s former bodyguard, Sergei Kosyrev, said in a YouTube video that he saw Putin in 1991 in Traber’s office at an antiquity shop in Lavrova Street (currently, Furshtatskaya Street) – and the office had a number of unofficial uses as well.

Notably, such companies as Sovex and its co-owner, Horizon International Trading, would not be able to operate without the contracts signed by Vladimir Putin himself. On May 17, 1996, Vladimir Putin signed Directive 488-R on the lease of the Pulkovo Bulk Fuel Installations to Sovex CJSC. Sovex enjoyed a monopoly on aircraft fueling in the Pulkovo Airport up to 2013.

De-facto co-owners of Petersburg Oil Terminal, Ilya Traber, and Sergei Vasilyev, have attended Putin’s birthday parties and received a warm welcome there. No other crime bosses have been honored this way

According to two of our sources, de-facto co-owners of Petersburg Oil Terminal, Ilya Traber, and Sergei Vasilyev, have attended Putin’s birthday parties. They visited at least two such parties, in 2004 and 2016, and received a warm welcome there. No other crime bosses have been honored this way: thus, Petrov was not even there, according to a source who witnessed the entire celebration.

Today, Ilya Traber is on an international wanted list, where Spain put him in 2016, states investigative prosecutor José Grinda of the Special Public Prosecutor’s Office against Corruption and Organized Crime. In the meantime, Russian prosecutors have tried making direct reports about “the violation of Traber’s rights,” taking on the role of Traber’s defense attorneys, whereupon the Spanish side lodged a formal protest.

Speaking of Sergei Vasilyev, his acquaintance disclosed to The Insider that the crime boss continues visiting Europe with an Italian visa.

As for Prince Albert II of Monaco, he failed to see “any hint of a lead” in Eringer’s report on the network of companies in Monaco and Liechtenstein connected to the Tambovskaya gang and Putin at the same time. However, His Highness joined Vladimir Putin on a trip to Tuva in 2007, participated in the Olympic Torch Relay in Sochi in 2014, and finally honored Vladimir Putin with the highest Monegasque award – the Order of Saint-Charles.

This article has first appeared in Russian at The Insider’s site.

Ilya Traber

Ilya Traber Michele Tecchia at a horserace, 2017 (second on the right)

Michele Tecchia at a horserace, 2017 (second on the right)

Mikhail Skigin

Mikhail Skigin Vladimir Yakunin and Gennady Timchenko

Vladimir Yakunin and Gennady Timchenko

“The day of the referendum that I observed in Barcelona gave me a lot to think about. The brutal action of the Spanish police was not surprising – thousands of them were deployed there for the likely purpose of blocking the vote. There is no reason in questioning the accuracy and honesty of the ballot counting. The most impressive thing about this referendum was an ability of Catalans to organize voting and counting based on effective grassroots organization. The significant role in this was played by the technical strategy: for example, the possibility of voting at any polling station was mentioned only during the beginning of the voting.

“The day of the referendum that I observed in Barcelona gave me a lot to think about. The brutal action of the Spanish police was not surprising – thousands of them were deployed there for the likely purpose of blocking the vote. There is no reason in questioning the accuracy and honesty of the ballot counting. The most impressive thing about this referendum was an ability of Catalans to organize voting and counting based on effective grassroots organization. The significant role in this was played by the technical strategy: for example, the possibility of voting at any polling station was mentioned only during the beginning of the voting.