The new round of sanctions against Russia’s authorities naturally begs the question: will they simply backfire, rallying Russia’s citizens around Putin and worsening the already-negative perception of the West? The answer depends on how tangible and bold those sanctions actually are. It also depends on how they are presented to Russian society – not only through state propaganda, but from the West as well, which has various means of conveying its own opinion to Russia’s population.

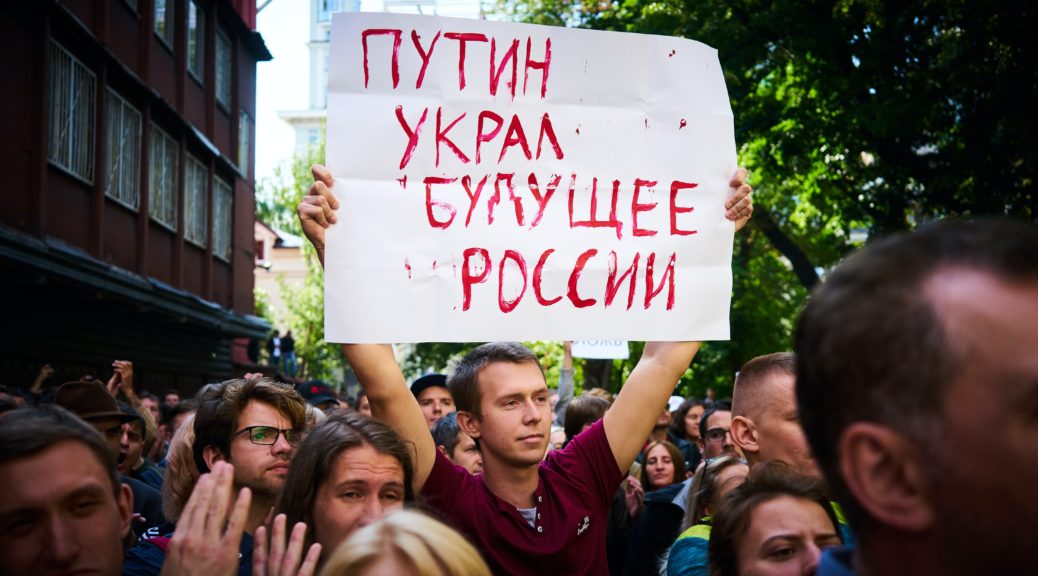

The key to understanding the true feelings of Russian society and its potential reactions to new sanctions might be found in Putin’s recent address to the Federal Assembly and his nearly simultaneous statements about de-escalating tensions on the Ukrainian border. It is important to not lose sight of the fact that since the early 2010s, Putin has not made a single effort to satisfy Russians who identify with the opposition. He prefers ignoring or intimidating anyone who expresses dissatisfaction with his politics. That is why he first and foremost addresses his base, and focuses on smoothing over his relationship with them and them alone.

The very fact that most of Putin’s address was dedicated to the social problems Russia face and promises to provide all kinds of payments and benefits, whereas the traditional threats to the West and foreign policy and ideology in general were a distant second and presented in a far more peaceful tone speaks volumes about the radical shifts taking place, not only in Putin’s head, but in Russian society as a whole.

First of all, the issue of confrontation with the West, the situation in Ukraine, and international policy are not interesting to Putin’s target audience, and may even annoy them. By all accounts, the night before his address, Putin received reliable information that Russian citizens do not want war on any scale. Not only that, they are so strongly and clearly against the idea, that they can no longer be ignored.

Secondly, Putin’s electorate is poor and does not enjoy a high quality of life. They are becoming increasingly disgruntled. Thus, Putin found himself forced to focus on promises for social assistance for the people, specifically some form of direct payments. He has now tied his own political prospects to his regime’s ability to satisfy growing social obligations in a context of increasing problems on the Russian economy.

Russian domestic politics have now been reduced to the most primitive formula: on the eve of the elections, Putin gives his electorate additional money from the budget, thereby buying their votes and general loyalty. He simply does not have any inspirational slogans or ideology to mobilize society.

As a result, international sanctions designed to hit at the Russian economy and state revenues will also strike a blow to the Putin regime. The minute he is unable to fulfill all of his obligations to the citizens, violence will be the only means left for him to hold onto power. But this time, things will be different – Putin will not just be fighting against the political opposition, but rather the vast swathes of society on which he has relied for the past two decades.

There is no doubt that Putin and his propaganda will attempt to blame the West for all of the trouble, but that approach is already starting to raise some eyebrows.

To begin with, the very idea that the West is capable of inflicting serious damage on the Russian economy through sanctions has broken down some of the peoples’ trust in Putin: it means he is not quite as all-powerful as he claims, and his reassurances that Russia is a strong, independent economy with no fear of any sanctions is nothing more than a lie. What’s more, the people will inevitably start to demand a normalization of relations with the West. Sociologists have already begun to note this phenomenon – if the sanctions are such a burden for Russia to bear, isn’t it time to start seeking paths toward reconciliation with the rest of the world? The ultimate goal of confrontation is inexplicable given that Russian society is decidedly not willing to engage in any wars.

It is important to note that the West has not yet pulled the lever that the Russian opposition has been offering it for many years – large-scale personal sanctions against Putin’s inner circle – Russia’s richest and most influential families, including that of the Russian President himself.

Striking such a blow to the main beneficiaries of the current Russian regime would resolve several issues at once. It would force oligarchs under sanctions to consider decisive steps aimed at removing Putin – if only to save their own capital and international businesses. It would also make it very difficult for Putin’s propaganda to leverage the sanctions to consolidate the electorate. Paradoxically, those who most support the capitalist economy are the same people who oppose Putin, as he relies on poor, embittered people with nostalgia for the USSR, who believe that capitalism and capitalists are evil. Harsh sanctions against the billionaires in Putin’s entourage will arouse nothing but Schadenfreude among these sectors of society, and any appeals for sympathy from the authorities will likely not go down well among those who are mainly concerned with simple survival. The effect will in fact be quite the opposite, once they begin to wonder why the authorities are suddenly so concerned about the very richest, while seemingly unbothered by the problems of the very poorest.

It is important to note that “sanctions against Russia” is a very unfortunate turn of phrase, which is often heard in official statements. This is a gift for Putin’s propaganda machine, and feeds fears about “Russophobia” in the West. In the context of today’s Russia, it would make more sense to talk about “sanctions against Putin,” or “sanctions against the Putin regime,” focusing on the fact that the West, its leaders, and people have nothing against Russia or its citizens, and that a free, democratic Russia and its people would be accepted as friends, partners, and allies. That kind of a shift in focus would make it easier to disseminate the idea in the widest sectors of the population and the administrative and economic elite that Putin is Russia’s problem, and denying him power is the quickest, and in fact the only path toward normalizing all areas of life in Russia.