Over the past several decades, the economy of the Russian Far East has become increasingly oriented toward serving China.

In March 2021, Vladimir Putin approved a new large-scale project for the Russian Railways to build hundreds of kilometers of rail tracks for exporting coal from Yakutia to China. The project will cost 700 billion rubles (around $9.5 billion) and additional money is needed to provide a power supply to the Tynda-Komsomolsk section of the railway and to develop the ports of the Vanino-Sovgavansky junction. Further, in April 2021, Russian Railways started the 340 km construction of second rail tracks on the Ulak-Fevralsk section of the Baikal-Amur Mainline. The Ulak station gives access to export markets for coal from the Elginsky Coal Mine in Yakutia.

Amur Oblast is crucial for China. Besides coal mining, the Amur region holds the Power of Siberia gas pipeline and the Eastern Siberia -Pacific Ocean (ESPO) oil pipeline, both of which run to China. The Amur region also houses the Zeiskaya, Bureyskaya, and Nizhne-Bureyskaya hydroelectric power plants which provide electricity both to the Amur region and the adjacent territories in China. Finally, another strategically important infrastructure project to Beijing is the Amur Blagoveshchensk-Heihe road bridge. In the future, Russia plans to build a railway bridge in the same direction. The governor of the Amur Oblast, Vasily Orlov, is actively promoting this project as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative that will primarily serve China’s interests.

The influence exerted by China on the economy of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast and Primorsky Krai is also notable. The agricultural sector of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast is almost entirely focused on producing soybeans for China. The railway bridge across the Amur Tongjiang-Nizhneleninskoye in the oblast allows for efficient export of this lucrative crop. Similarly, in the Primorsky Krai, the seaports, the agricultural sector, the logging industry, and the fishing industry are critical for the PRC.

China seeks to control the extraction and export of natural resources in the region. This can be seen prominently in the Far East’s logging industry, a sector that is under complete control of Chinese businesses. Chinese companies buy wood, primitively saw it, and control the wood quality before sending it to the PRC. The sales of round timber are the most profitable even with the intermediaries’ share, so China has no incentives to develop deep wood processing in Russia. In addition, China is not interested in purchasing processed products since it has plenty of timber processing plants in the border provinces.

The infrastructure of the Far East

The construction of a road bridge across the Amur River between Russia and China in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast is almost complete. Around six million tons of cargo are expected to pass through the bridge annually, and the flow of passengers should be approximately 3 million people per year. The length of the bridge is a little over a kilometer, and the total length of the crossing is 20 km (6 km of roads in China and 14 km of roads in Russia). The cost of the project is about 18.8 billion rubles ($256.6 million). Instead of budget funds, a concession model was used to finance the project. This provides for the construction and operation of the bridge on a commercial basis during the first 20-year billing period of the bridge’s existence. After a three-year construction period an enterprise will be permitted to collect tolls on the bridge for the first sixteen years of operation.

In Amur Oblast, Blagoveshchensk is the only regional center in Russia located on the Chinese border. The Amur River separates Blagoveshchensk and the Chinese city of Heihe. The construction of the first cross-border road bridge in the Blagoveshchensk region was completed in December 2019. Now, Russia and China are considering constructing a railway bridge in the same direction. The decision on this will be made after evaluating the economic efficiency of the road bridge. Overall, the construction of these bridge crossings will tie the transport infrastructure of the Russian Far East to China. However, China will be the one to benefit from these projects primarily.

A similarly asymmetric interaction between Russia and China can be seen in how China stands to receive economic benefits from the Power of Siberia gas pipeline and the ESPO oil pipeline for many years to come. The agreement on the oil export which established this relationship was signed in 2009. In exchange for $15 billion and $10 billion loans from the China Development Bank for Rosneft and Transneft respectively, the Russian state-owned companies pledged to supply China with 15 million tons of oil annually through the ESPO from 2011 to 2030.

Moreover, Rosneft and Transneft have provided the Chinese company CNPC with a discount of $1.5 per barrel causing Rosneft to lose about $3 billion. Therefore, it was clear from the start that China was dictating the terms under which these pipelines would operate.

As for the gas export to China, the experts say that the Power of Siberia will not pay off for its Russian creators until 2030. According to RusEnergy’s calculations, the total costs of the Power of Siberia, including the development of fields, the construction of pipelines and gas processing plants in wild taiga, the crossing near the Amur River, etc., will amount to about $100 billion. This will be almost double Gazprom’s $55 billion cost estimate. When it comes to natural gas, China is a unique consumer – it is not a “monopoly” but rather a “monopsony,” meaning that the PRC as the sole buyer in the market sets its own terms.

The Power of Siberia, which is about three thousand kilometers in length, transports gas from the Irkutsk and Yakutsk gas production centers to Russian consumers in the Far East and, crucially, to China. The parties determined the terms of the partnership in an intergovernmental agreement in October 2014, and the gas supplies started flowing in December 2019. Russia is the second biggest gas supplier to China after Turkmenistan. Gas exports to China via this pipeline in 2020 amounted to 4.1 billion cubic meters. In 2021, the supplies are expected to double. The planned level of supplies for the Power of Siberia is 38 billion cubic meters per year. Still, China and Russia are discussing the possibility of increasing the maximum supply volume by another 6 billion cubic meters.

In the first quarter of 2020, the price for a thousand cubic meters was $202. In January 2021, the price fell significantly and is now below $120. Of all pipeline gas suppliers, Russia exports gas to China at the lowest price. In comparison, in January 2021, Turkmenistan received $187 per thousand cubic meters for its gas, Kazakhstan for $162, Uzbekistan for $151, and Myanmar for $352.

Additionally, the Amur Gas Processing Plant (GPP) is one of Gazprom’s most significant infrastructure projects in the Russian Far East. This plant will process multicomponent natural gas from the Yakutsk and Irkutsk gas production centers supplied through the Power of Siberia gas pipeline. Valuable components extracted during processing will become raw materials for enterprises in the gas, chemical, and other industries. The capacity of the plant will be 42 billion cubic meters of gas per year. The GPP will also include the world’s largest helium production venue, producing up to 60 million cubic meters per year. In addition to natural gas and helium, the plant’s commercial products will include ethane, propane, butane, and pentane-hexane fraction. The plant will consist of six processing lines, and the launch of the first two is scheduled for 2021. Gazprom will be gradually introducing the rest of the lines in the next four years. Thus, the plant will start working at its total capacity by the end of 2025.

In 2020, Russian company SIBUR and Chinese company Sinopec signed an agreement on creating a joint venture on the Amur Gas and Chemical Complex (AGCC). It is one of the world’s largest plants producing base polymers with a total capacity of 2.7 million tons per year. Russian’s share in the deal will be 60%, and Chinese will be 40%. The construction of the complex will be synchronized with Gazprom’s Amur GPP, so that both reach full capacity by 2025. The supply of ethane and liquefied hydrocarbon gas from Amur GPP will provide the AGCC with raw materials for further processing into high-value-added products. Due to the geographic location of the complex, the AGCC’s products will be focused primarily on the PRC market, the largest consumer of polymers in the world. The budget of the Amur Gas Chemical Complex is estimated at $10-11 billion.

Timeline: Export of electricity to China

1992 A 110 kV transmission line “Blagoveshchensk-Heihe,” connecting the power systems of Russia and China, was built. Electricity exports to China began at 30-160 million kWh per year.

2005 A long-term cooperation agreement was signed between the Unified Energy Systems (UES) of Russia and the State Grid Corporation of China.

2007 Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Hu Jintao signed a joint declaration “Supporting Major Energy Projects.” This document outlined Russian-Chinese energy cooperation’s fundamental principles and approaches.

2009 Russian Eastern Energy Company (EEC) and the State Grid Corporation of China signed a contract to supply China with electricity via the existing 220 kV Blagoveshchenskaya-Aigun and 110 kV Blagoveshchensk-Heihe transmission lines. The total volume of annual electricity supplies that year amounted to 854 million kWh.

2011 Russian company EEC built a 500-kV power transmission line, “Amurskaya-Heihe,” which connected the Amur Region of Russia and the north-eastern regions of the PRC with an interstate ultrahigh voltage power transmission line. The project made it possible to significantly increase the export of electricity to China, which amounted to 1.24 billion kWh that year.

2012 A 25-year contract was signed to supply China with electricity in a total volume of 100 billion kWh. In June, the State Electric Grid Corporation of China and Inter RAO signed a memorandum on expanding electric power cooperation. Electricity exports to China in 2012 amounted to 2.63 billion kWh.

2013 An agreement to expand Russian-Chinese electricity cooperation was signed. The document envisages the complex projects for the development of coal resources in the Russian regions of the Far East, the construction of large thermal power plants, and ultra-high voltage power lines to increase the volume of electricity supplies to China. Electricity exports in 2013 amounted to 3.495 billion kWh.

Ou Xiaoming, the representative of the Russian branch of the State Grid Corporation of China, said at the Russian Energy Week international forum that in the future, the volume of electricity imports from Russia to China would not change.

Chinese investments in the economy of the Russian Far East

The Russian Central Bank (CB) publishes official statistics on foreign investments in Russia. According to the CB, the presence of Chinese capital in the economy of the Far East is surprisingly negligible. As of July 2019, China’s share in the total accumulated foreign investment in the region was only 0.8% ($530 million). For reference, Cyprus’s investments in the Far East amounted to $4.1 billion.

The specifics of the CB’s calculations explain this seeming absence of Chinese investment. The CB does not take small business investments and informal business activity into account. In addition, the Central Bank’s data does not trace the investors in offshore schemes, which account for up to 95% of foreign investments in the Far East region. As a result, many Chinese enterprises appear in the official data as Russian or, for example, Bahamian.

However, the data of the Ministry for the Development of the Russian Far East tell a very different story. According to the Ministry, at the end of 2019, China’s share in the total volume of foreign direct investment in the region was 63% (45 projects worth $2.6 billion). In 2017, the investments were $4 billion.

This large difference can perhaps be explained by the fact that the Ministry simply summed up the announced project estimates without investigating how much money actually got into the region. In other words, it is impossible to know precisely how significant the Chinese investment in the Far East of Russia actually is. Yet, it can be claimed with some certainty that the real numbers are higher than the official ones but less than those publicly announced by Chinese and Russian officials.

Agriculture, forestry, and construction are the three pillars of Chinese capital in the Far East. Small and medium-sized Chinese companies in the Far East have extensive experience doing business and supporting informal relations with their Russian counterpart s. Many Russian and Chinese entrepreneurs are family friends who send their children to study with each other. As a result, a solid foundation for cross-border investment has been formed.

Chinese migration

According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia, for the first half of 2019, one in every ten foreigners coming to Russia were Chinese citizens. During this time, 863, 000 Chinese citizens were registered for migration, which was 30% more than in the first half of 2018.

The informational and analytical agency “East of Russia” analyzed the Ministry of Internal Affairs data and discovered that there are more Chinese people among the foreign employees who got work quotas than those from other nations. Indeed, the Ministry of Labor issued more than half of all quotas for this region to Chinese citizens, but the actual numbers are relatively modest – 27.8 thousand people. Overall, at the end of the first half of 2019, 39.8 thousand Chinese had a valid work permit in Russia. These documents are usually valid for a few months.

Russians’ attitudes towards the Chinese migration is generally negative. According to the Levada Center poll published in September 2019, more than half of Russians (53%) favored limiting Chinese migration. 28% of those surveyed were ready to let Chinese people in the Russian Federation only temporarily, and 25% were in favor of a complete ban on the arrival of Chinese citizens in the country. Only 19% of the respondents were ready to see immigrants from China among the residents of Russia.

The main risk of the Chinese migration in the Far East is that the number of Chinese people permanently living in the region can increase due to their shared border of the Amur River. This could happen quickly with the construction of two bridges across the Amur in the Amur Oblast and the Jewish Autonomous Oblast. Most importantly, the Chinese (both who live in the Russian Far East and those who live in the border provinces of China) consider the Russian Far East to be historically Chinese land.

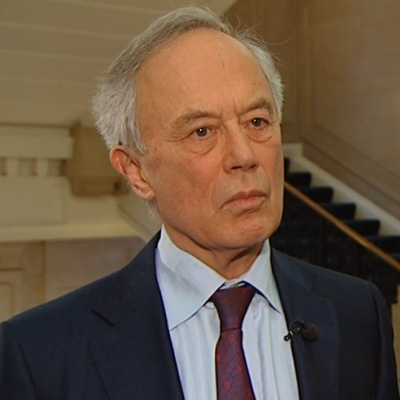

Yuri Moskalenko

Andreas Umland, a German political analyst, an expert of the Euro-Atlantic Cooperation Institute specializing in Russian ultra-nationalism and authoritarianism identifies three possible reasons why such an escalation could occur right now. The first and most common version is a decrease in Putin’s rating and the need to divert attention from socio-economic problems with yet another demonstration of power. The second possible reason is the probability of the existence of the project on turning the Sea of Azov into the inner Russian sea and the desire to negatively affect the Ukrainian economy by the blockade of ports in Berdyansk and Mariupol. And the third possible reason concerns the news that the construction of the brand-new Kerch Bridge is allegedly shifted. Accordingly, a new attack could have been undertaken in order to divert attention from the news damaging the reputation of the Russian authorities.

Andreas Umland, a German political analyst, an expert of the Euro-Atlantic Cooperation Institute specializing in Russian ultra-nationalism and authoritarianism identifies three possible reasons why such an escalation could occur right now. The first and most common version is a decrease in Putin’s rating and the need to divert attention from socio-economic problems with yet another demonstration of power. The second possible reason is the probability of the existence of the project on turning the Sea of Azov into the inner Russian sea and the desire to negatively affect the Ukrainian economy by the blockade of ports in Berdyansk and Mariupol. And the third possible reason concerns the news that the construction of the brand-new Kerch Bridge is allegedly shifted. Accordingly, a new attack could have been undertaken in order to divert attention from the news damaging the reputation of the Russian authorities. Mikhail Gonchar, director of the Centre for Global Studies “Strategy XXI”, adds that the situation should be looked at much wider than just the conflict between the two neighboring countries. Russia claims the leading world position and in every way demonstrates to the west its strength, checking the limits of what is permitted. In addition to the Ukraine and Syria cases, as well as the case of Skripals, Mikhail also cites a recent example of failures in the GPS navigation system in Norway and Finland, which resulted in that the Norwegian frigate rammed the Finnish tanker during NATO exercises in Norway. According to the Presidents of both countries, the reason was the deliberate creation of GPS-interference from the Russian side. Mikhail Gonchar claims that Ukraine in this chain of events is just an element of a more global policy of Russia’s aggression against the West.

Mikhail Gonchar, director of the Centre for Global Studies “Strategy XXI”, adds that the situation should be looked at much wider than just the conflict between the two neighboring countries. Russia claims the leading world position and in every way demonstrates to the west its strength, checking the limits of what is permitted. In addition to the Ukraine and Syria cases, as well as the case of Skripals, Mikhail also cites a recent example of failures in the GPS navigation system in Norway and Finland, which resulted in that the Norwegian frigate rammed the Finnish tanker during NATO exercises in Norway. According to the Presidents of both countries, the reason was the deliberate creation of GPS-interference from the Russian side. Mikhail Gonchar claims that Ukraine in this chain of events is just an element of a more global policy of Russia’s aggression against the West.